Dorian Gray

(Michael K.)

I had a really hard time deciding which book to read before seeing The Picture of Dorian Gray on Broadway last week.

You might be thinking: “Are you stupid? It is based on a book. Read that book.”

“Okay,” I would answer, “but which edition? Which version? Which of my dozen copies?!”

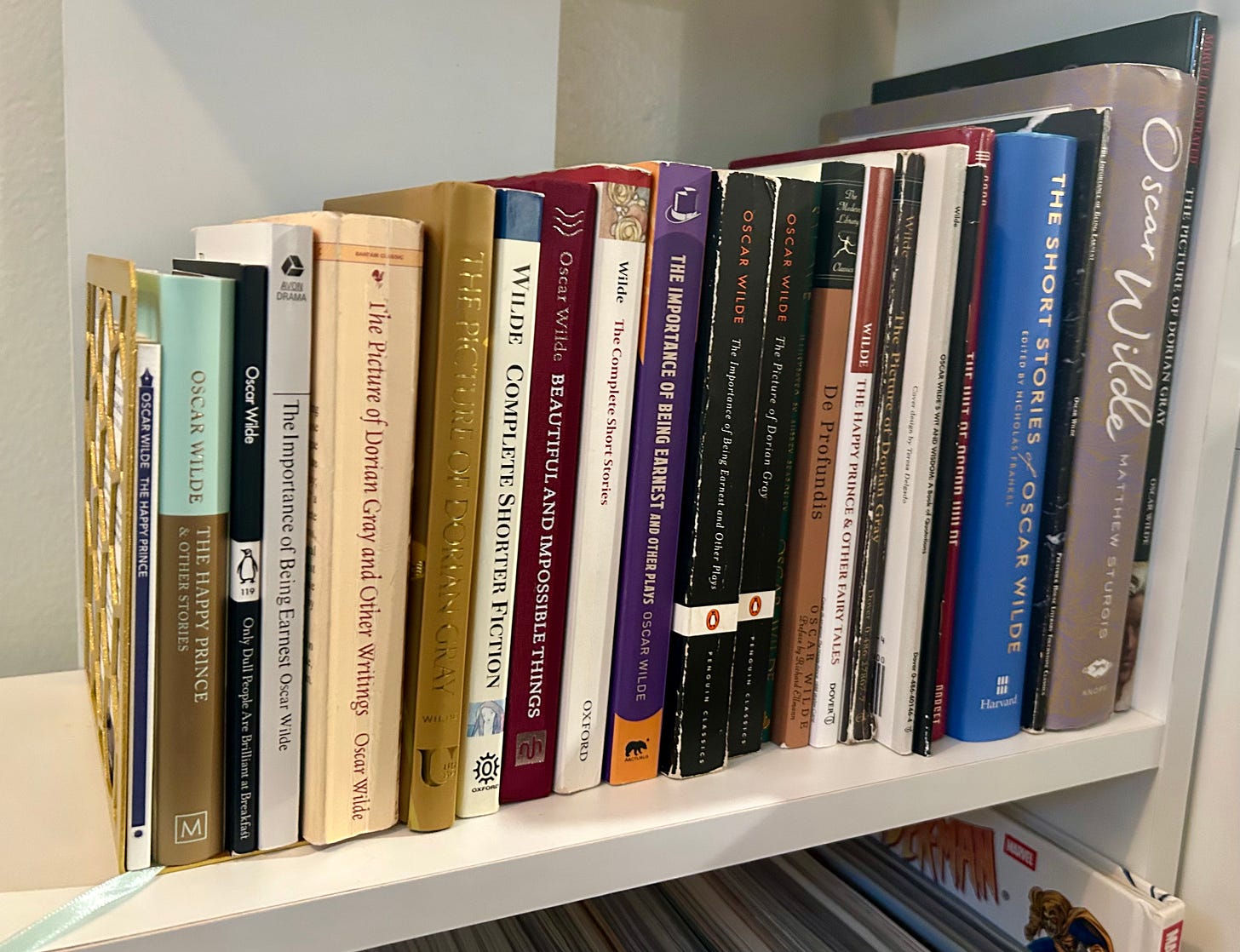

As with many collections, it’s hard to say when mine began. It was certainly over a decade ago and I know it began with just that one book, collecting different copies of The Picture of Dorian Gray. I think I only expanded to other Oscar Wilde writings when I found an old edition of Salome in an antique store and simply had to have it.

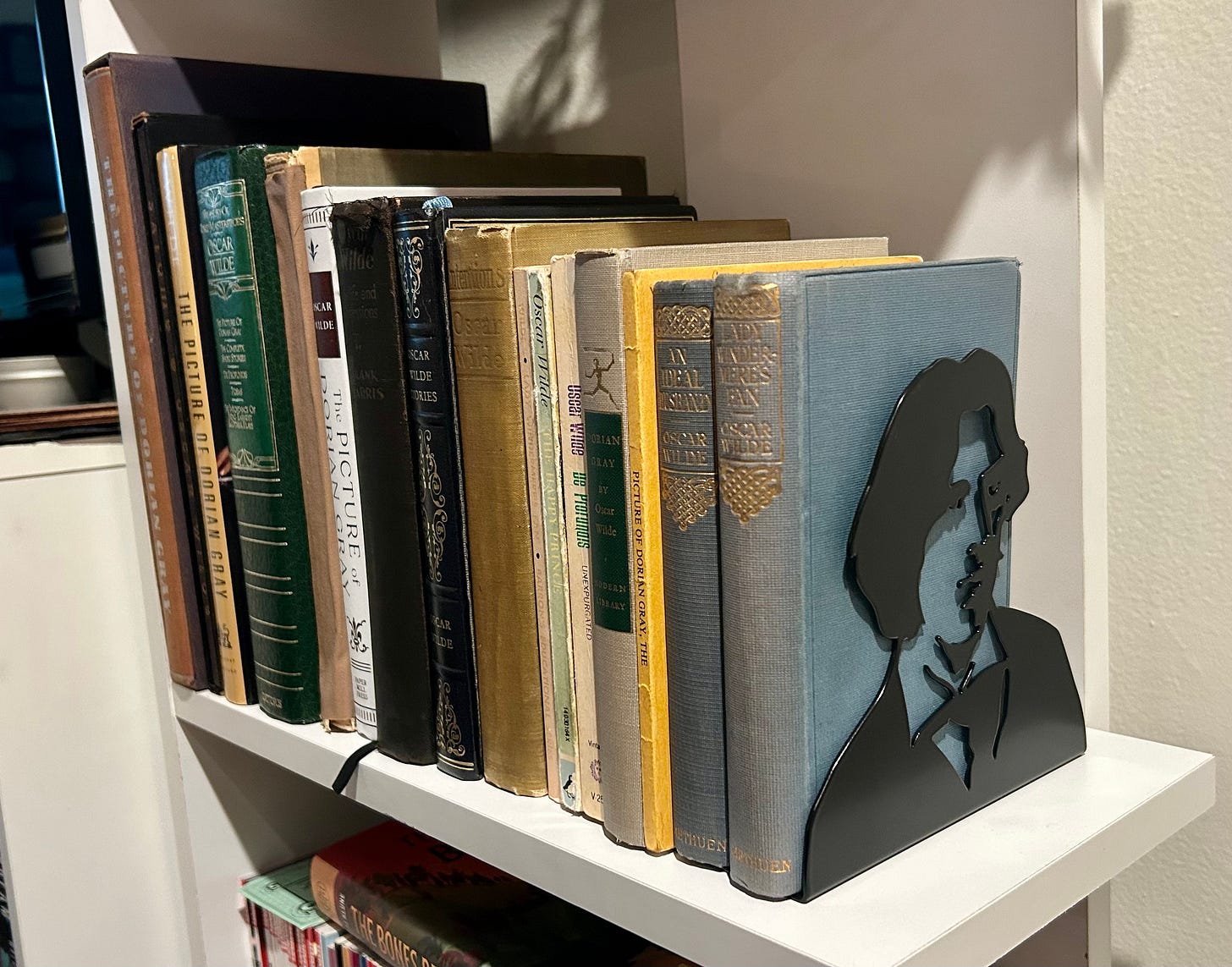

Now, my Oscar Wilde collection takes up more than two shelves in my home and includes antique copies and new editions, annotated versions, stories grouped into various collections. I have quotation books, biographies of Wilde, even biographies of other people associated with him.

But when I decided to fly to New York to see the award-winning play before it closed — a 30th birthday gift from myself and from my parents — I realized it had been close to a decade since I’d read that first book I fell in love with. It was time for a reread.

The copy I ended up choosing was this: The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray, published by Belknap Press in 2012. According to a receipt stuck between pages, I bought this copy only a year after its publication. I was a freshman in college on a spring break trip with my dad — coincidentally, also in New York. I’ve had this particular copy for about a dozen years. It must be one of my earliest.

It felt like an apt choice for that reason and for one other: it is the closest edition we have to Oscar Wilde’s original intention.

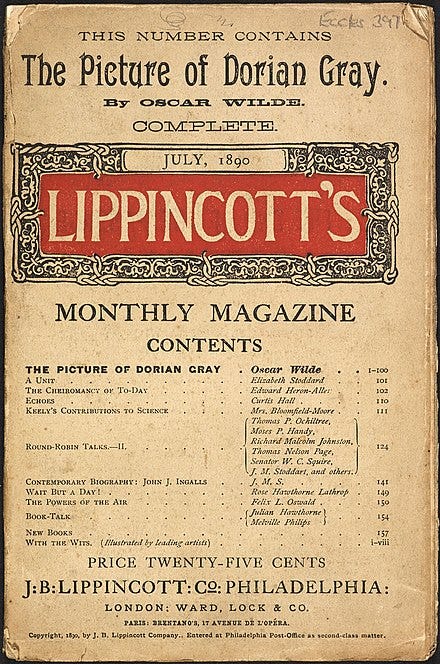

The Picture of Dorian Gray exists in multiple forms. It was first published in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine as a shorter and freer piece of work, 13 chapters to its eventual 20. Lippincott’s made a number of edits before publishing that shorter version, and even more were made before the story was expanded and published as a full novel.

The expanded novel version is arguably a better narrative — elements are added, themes are sharpened, character arcs are heightened — but it is less his. It has been sanded down and molded by editors, reviewers, and public opinion into something that’s just a little bit… less.

So that’s what I read before going to see Sarah Snook tell the story on Broadway: the original, the closest thing we have to the story Oscar Wilde wanted to tell, before Lippincott’s edits, before the novel expansion and further edits, before reviewers reamed him out and he made adjustments in response.

This original uncensored pre-Lippincott version is Dorian Gray at its purest. It has fewer shocking scenes, yet is notably more scandalous. It’s much, much gayer. (Though that, of course, is all relative. To a modern reader, it’s mostly subtext and allusion and winking references.)

The Broadway production followed the most popular version, of course: the finished and edited novel. We get to see Dorian’s country estate at Selby Royal, rather than just hearing about it. We get the subplot of Sybil Vane’s brother James seeking revenge, which further pushes Dorian’s spiral at the end. We get the opium dens, physical manifestations of Dorian’s sins.

We also lose some things in the adaptation. (I feel the need to say here that my one and only qualm with the show is that there were moments that were hard to make out — Snook talks fast and frantic and the sound mixing at times is muddy. So it’s possible that one or two of these were present after all, but got lost to me in the hectic movement.): We lost Hetty Merton, the last girl he has an affair with before seeking redemption or relief. We lost Sybil and James’s mother, Mrs. Vane (which is fine, she’s annoying). We lost the wildly anti-Semitic theater manager (he’s still there, just no longer a “hideous”, “greasy”, “horrid old Jew”, thank goodness…). We lost a couple other characters like the frame-maker and his assistant, presumably cut for simplicity.

All of these changes made perfect sense to me. Not only were the characters unnecessary, but (with the exception of the innocuous frame-maker and his assistant), I think they actively detracted from the themes of the story. (Why would Hetty Merton be Dorian’s impetus for anything, we have never heard of her before…)

But the adaptation also added some elements back into the story from the original Lippincott’s work. (I’m pretty sure. I haven’t yet bought a copy of the script, so I can’t double check… (I’m so excited to find it at my local theater bookstore The Understudy when I get home from New York.))

Writer/director Kip Williams injected back into the story the more overt queerness that editors and reviewers and the public forced Oscar Wilde to remove. Key lines refer only to men, rather than men and women. (At Wilde’s “gross indecency” trials — aka trials for doing gay stuff — the Dorian Gray lines quoted as evidence were from the Lippincott’s original, rather than the notably less-gay final novel.)

He did not add back in, however, what is perhaps the most explicitly gay line in the original work: “It is quite true I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man should ever give to a friend. Somehow I have never loved a woman… I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly…”. I can’t explain that choice — it seems like the addition would have been in line with the other changes made. But what do I know! Williams (who is gay) seemed satisfied to communicate queerness in other ways instead.

All of that sexual attraction, the yearning undertones of the entire story, is certainly present in the stage adaptation. Of course, on stage, we have the benefit of facial expressions, tone of voice, and non-verbal vocalizations to communicate. Sarah Snook used all of those to convey queer attraction in the triangle of lust that is the three main characters.

Her Dorian Gray blushes, giggles, and ogles at Lord Henry. Her Lord Henry smirks knowingly at both Dorian and Basil. Her Basil Hallward looks longingly at Dorian, face contoured by unrequited love. The stage play turns Basil’s worship of Dorian from that of an artistic Platonic ideal (as the expanded novel claims) back into the romantic and sexual longing that is present in Wilde’s original.

The stage adaptation also heightens another element of the book, a central theme that is what keeps me coming back to this story again and again: the relationship between art and life.

The whole book is about that relationship, more than anything else. Quite literally, the art receives the consequences of life’s sins in the form of wrinkles and monstrosity.

But also, the reverse happens. Dorian is, first to those around him and then in his own mind, a work of art, thanks to his beauty and lasting youth. Much of Oscar Wilde’s work as a whole talks about this: Aestheticism, art and beauty for its own sake, and (as the introduction to this edition of Dorian Gray says) “art and its proper relationship to life”.

That introduction also says the following about that relationship: “By confusing the relations between life and art—to the degree that he becomes the work of art and feels he can act with impunity as a result—Dorian has allowed…his humanity to become diminished”.

Dorian himself is a metaphor for this idea: “The minute life mistakes its object and tries to be sensation or art, to act wholly according to it or to separate itself from those broader elements that define humanity as such, a kind of corruption sets in and both life and art become inescapably spoiled in consequence.”

The direction of The Picture of Dorian Gray on Broadway manifested this idea beautifully. By using live cameras to translate onstage movement onto screens projected for the audience, the show automatically turns the characters into stylized versions of themselves.

The hook for this production is that Sarah Snook plays all 26 characters by herself. And that is an incredible feat in and of itself. But what fascinated me was how she does it and how that changes — and how that reflects the changing relationship between art and life in the story.

Snook’s character changes start as physical: first, she wears black clothing rather than a costume and only changes her voice, acting into different cameras to distinguish between characters; then, her characters change still through physical means, using wigs and costumes; by the end of the play, she is using technology like camera filters and face-tune to change her appearance, filmed in selfie mode.

She also mostly stops changing her costumes somewhere around Dorian’s adulthood, where she stays dressed as him, stuck as he is in his own narcissism. Dorian is performing himself as Snook is performing him through more and more heightened means, more stylized, more dramatized.

His life is not a life — it’s a piece of art.

The screens also grow more and more heightened, proliferating across the stage over the course of the play. It helps the humorous chaos give way to a frightening and painful chaos as Dorian’s character arc demands it. The number and usage of screens also grows as Dorian’s life becomes more and more a performance.

Again, more art than life.

This story is always worth reading (or watching), I believe, but perhaps now especially. Now in this era of renewed book banning and scrutinizing queer stories, interpretations of Dorian Gray take on new consequence.

Of course, there’s the censorship of the original. The eventual published novel is notably different than Wilde’s intended story, due almost entirely to censorship (both by editors and public opinion).

To me, this is a reminder to vocally and financially support queer stories. The editors and Oscar Wilde bent to public pressure — a fury around some infamous scandals like the Cleveland Street scandal plus some good old-fashioned homophobia and Victorian sexual morality. If public pressure is instead in support of queer voices and non-conforming stories, think about what incredible art there could be!

I also think it’s worth thinking about Wilde’s main theme: what is the purpose of art? Is it beauty for beauty’s sake? Is there always inherently a deeper meaning?

I personally think that yes, there’s always inherently a deeper meaning. Even if the art is not intentionally political, even if the art intends to be only beauty for beauty’s sake, everything about it is political. The choice of subject, the point of view, the inherent biases of the artist, the voices included and not included. Everything is political and art is far from an exception.

On another, and final, personal note: I often struggle with something that we see Dorian struggle with. (It’s not the narcissism, don’t worry.) It’s the desire to see life through the lens of art.

I find myself seeking good stories in my life, sometimes at the expense of authentic life choices. I was telling a friend this recently, in fact, that often when I find myself attracted to a person, I have to pause and ask: is it the person I’m interested in, or is it the story?

Whether the story is real or whether there is a character I’ve constructed from the person in my mind, I have to be careful to not confuse that with reality. I have failed before, entered relationships where the story was seductive and clouded my perception of the person.

The better I know myself, the more my love for Oscar Wilde and Dorian Gray makes sense to me. The queerness of it all, for sure, and the witty yet insightful Victorian Gothic writing, but also the complex blurry boundaries between art and life, stories and reality, that permeates and feels a little too familiar for comfort.

Okay that’s all for today. I love Oscar Wilde and also you!

<3 Isabel

p.s. here’s a short playlist I made for The Picture of Dorian Gray:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to You Signed Up For This to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.